Call:

rpart(formula = Species ~ ., data = iris)

n= 150

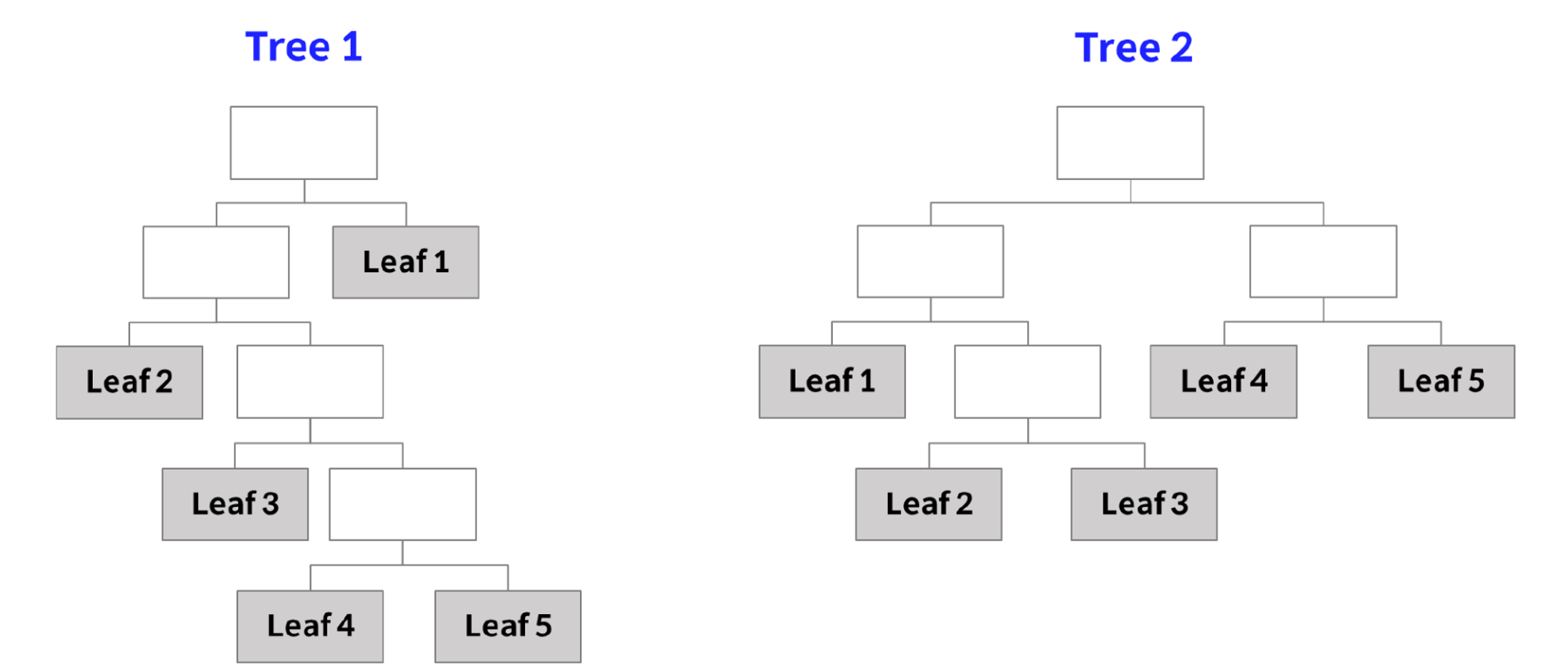

CP nsplit rel error xerror xstd

1 0.50 0 1.00 1.18 0.05017303

2 0.44 1 0.50 0.70 0.06110101

3 0.01 2 0.06 0.09 0.02908608

Variable importance

Petal.Width Petal.Length Sepal.Length Sepal.Width

34 31 21 14

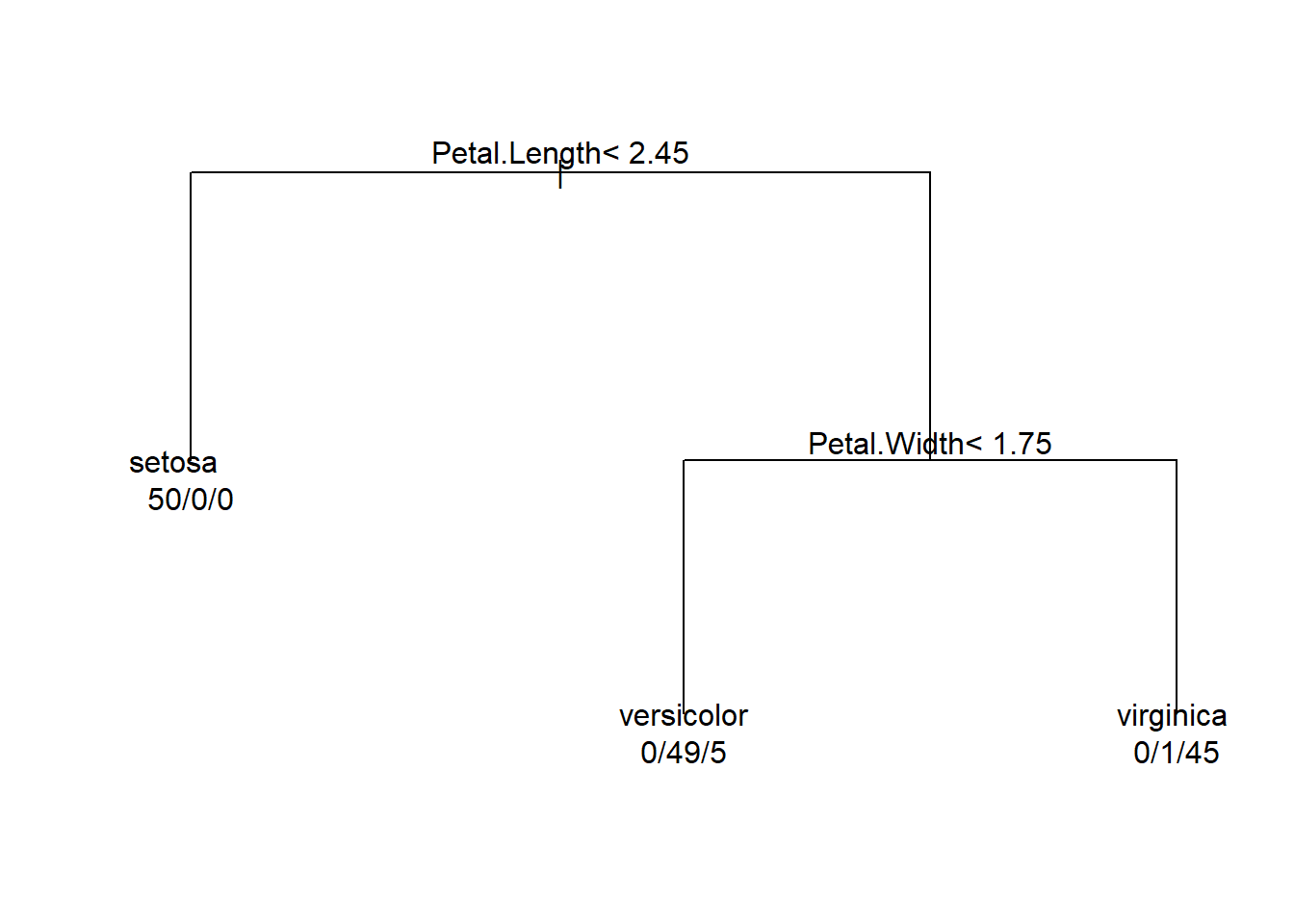

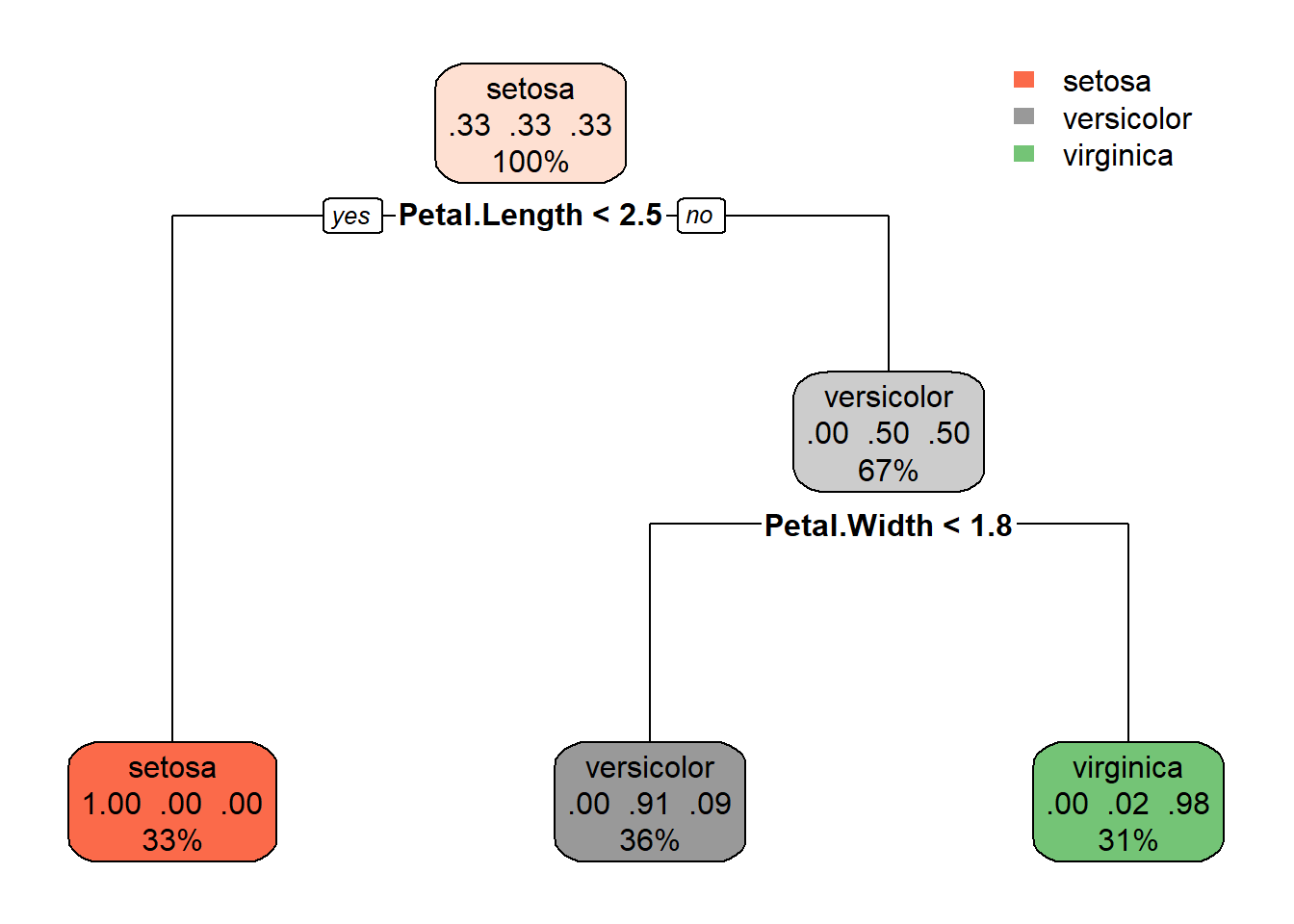

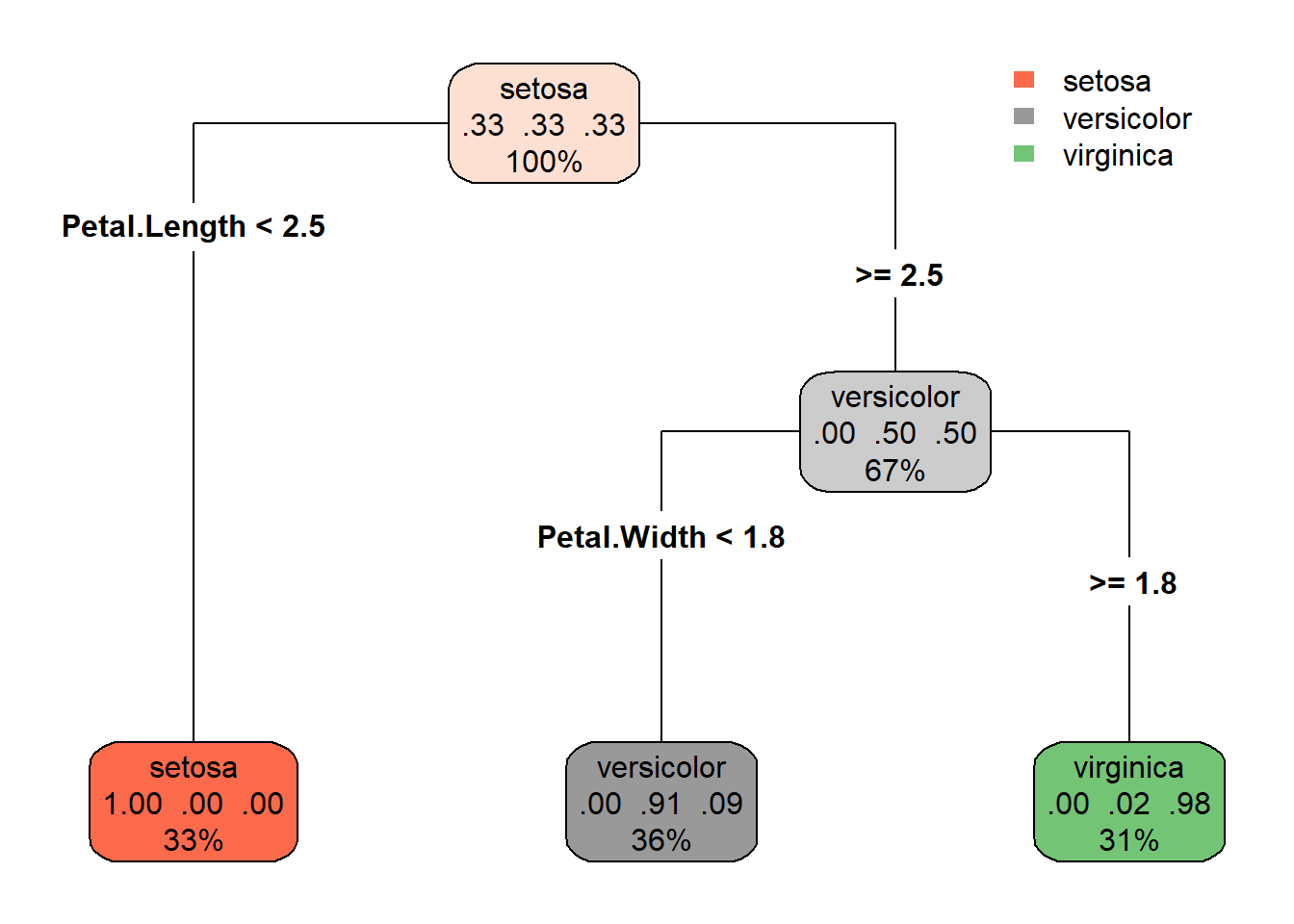

Node number 1: 150 observations, complexity param=0.5

predicted class=setosa expected loss=0.6666667 P(node) =1

class counts: 50 50 50

probabilities: 0.333 0.333 0.333

left son=2 (50 obs) right son=3 (100 obs)

Primary splits:

Petal.Length < 2.45 to the left, improve=50.00000, (0 missing)

Petal.Width < 0.8 to the left, improve=50.00000, (0 missing)

Sepal.Length < 5.45 to the left, improve=34.16405, (0 missing)

Sepal.Width < 3.35 to the right, improve=19.03851, (0 missing)

Surrogate splits:

Petal.Width < 0.8 to the left, agree=1.000, adj=1.00, (0 split)

Sepal.Length < 5.45 to the left, agree=0.920, adj=0.76, (0 split)

Sepal.Width < 3.35 to the right, agree=0.833, adj=0.50, (0 split)

Node number 2: 50 observations

predicted class=setosa expected loss=0 P(node) =0.3333333

class counts: 50 0 0

probabilities: 1.000 0.000 0.000

Node number 3: 100 observations, complexity param=0.44

predicted class=versicolor expected loss=0.5 P(node) =0.6666667

class counts: 0 50 50

probabilities: 0.000 0.500 0.500

left son=6 (54 obs) right son=7 (46 obs)

Primary splits:

Petal.Width < 1.75 to the left, improve=38.969400, (0 missing)

Petal.Length < 4.75 to the left, improve=37.353540, (0 missing)

Sepal.Length < 6.15 to the left, improve=10.686870, (0 missing)

Sepal.Width < 2.45 to the left, improve= 3.555556, (0 missing)

Surrogate splits:

Petal.Length < 4.75 to the left, agree=0.91, adj=0.804, (0 split)

Sepal.Length < 6.15 to the left, agree=0.73, adj=0.413, (0 split)

Sepal.Width < 2.95 to the left, agree=0.67, adj=0.283, (0 split)

Node number 6: 54 observations

predicted class=versicolor expected loss=0.09259259 P(node) =0.36

class counts: 0 49 5

probabilities: 0.000 0.907 0.093

Node number 7: 46 observations

predicted class=virginica expected loss=0.02173913 P(node) =0.3066667

class counts: 0 1 45

probabilities: 0.000 0.022 0.978